General Resolution: Why the GNU Free Documentation License is not suitable for Debian main

- Time Line

- Proposer

- Seconds

- Text

- Amendment Proposer A

- Amendment Seconds A

- Amendment Text A

- Amendment Proposer B

- Amendment Seconds B

- Amendment Text B

- Quorum

- Data and Statistics

- Majority Requirement

- Outcome

Time Line

| Proposal and amendment | Sunday, 1st January, 2006 | Thursday, 9th February, 2006 |

|---|---|---|

| Discussion Period: | Friday, 10th February, 2006 | Saturday, 25th February, 23:59:59 UTC, 2006 |

| Voting Period | Sunday 26th February, 00:00:01 UTC, 2006 | Sunday 12th March, 00:00:01 UTC, 2006 |

Proposer

Anthony Towns [[email protected]]

Seconds

- Manoj Srivastava [[email protected]]

- Russ Allbery [[email protected]]

- Steve Langasek [[email protected]]

- Kalle Kivimaa [[email protected]]

- Roger Leigh [[email protected]]

Text

Choice 1. The actual text of the GR is:

(0) Summary

Within the Debian community there has been a

significant amount of concern about the GNU Free

Documentation License (GFDL), and whether it is, in

fact, a free

license. This document attempts to

explain why Debian's answer is no

.

It should be noted that this does not imply any

hostility towards the Free Software Foundation, and

does not mean that GFDL documentation should not be

considered free enough

by others, and Debian itself

will continue distributing GFDL documentation in its

non-free

section.

(1) What is the GFDL?

The GFDL is a license written by the Free Software Foundation, who use it as a license for their own documentation, and promote it to others. It is also used as Wikipedia's license. To quote the GFDL's Preamble:

The purpose of this License is to make a manual, textbook, or other functional and useful document

freein the sense of freedom: to assure everyone the effective freedom to copy and redistribute it, with or without modifying it, either commercially or noncommercially. Secondarily, this License preserves for the author and publisher a way to get credit for their work, while not being considered responsible for modifications made by others.

This License is a kind of

copyleft, which means that derivative works of the document must themselves be free in the same sense. It complements the GNU General Public License, which is a copyleft license designed for free software.

(2) How does it fail to meet Debian's standards for Free Software?

The GFDL conflicts with traditional requirements for free software in a variety of ways, some of which are expanded upon below. As a copyleft license, one of the consequences of this is that it is not possible to include content from a document directly into free software under the GFDL.

The major conflicts are:

(2.1) Invariant Sections

The most troublesome conflict concerns the class of invariant sections that, once included, may not be modified or removed from the documentation in future. Modifiability is, however, a fundamental requirement of the DFSG, which states:

3. Derived Works

The license must allow modifications and derived works, and must allow them to be distributed under the same terms as the license of the original software.

Invariant sections create particular problems in reusing small portions of the work (since any invariant section must be included also, however large), and in making sure the documentation remains accurate and relevant.

(2.2) Transparent Copies

The second conflict is related to the GFDL's requirements for

transparent copies

of documentation (that is, a copy of the

documentation in a form suitable for editing). In particular,

Section 3 of the GFDL requires that a transparent copy of the

documentation be included with every opaque copy distributed, or

that a transparent copy is made available for a year after the

opaque copies are no longer being distributed.

For free software works, Debian expects that simply providing the source (or transparent copy) alongside derivative works will be sufficient, but this does not satisfy either clause of the GFDL's requirements.

(2.3) Digital Rights Management

The third conflict with the GFDL arises from the measures in Section 2 that attempt to overcome Digital Rights Management (DRM) technologies. In particular, the GFDL states that You may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies you make or distribute. This inhibits freedom in three ways: it limits use of the documentation as well as distribution, by covering all copies made, as well as copies distributed; it rules out distributing copies on DRM-protected media, even if done in such a way as to give users full access to a transparent copy of the work; and, as written, it also potentially disallows encrypting the documentation, or even storing it on a filesystem that supports permissions.

(3) Why does documentation need to be Free Software?

There are a number of obvious differences between programs and

documentation that often inspire people to ask why not simply

have different standards for the two?

For example, books are

often written by individuals, while programs are written by

teams, so proper credit for a book might be more important than

proper credit for a program.

On the other hand, free software is often written by a single

person, and free software documentation is often written by a

larger group of contributors. And the line between what is

documentation and what is a program is not always so clear

either, as content from one is often needed in the other (to

provide online help, to provide screenshots or interactive

tutorials, to provide a more detailed explanation by quoting

some of the source code). Similarly, while not all programs

demonstrate creativity or could be considered works of

art

, some can, and trying to determine which is the case

for all the software in Debian would be a distraction from our

goals.

In practice, then, documentation simply isn't different enough to warrant different standards: we still wish to provide source code in the same manner as for programs, we still wish to be able to modify and reuse documentation in other documentation and programs as conveniently as possible, and we wish to be able to provide our users with exactly the documentation they want, without extraneous materials.

(4) How can this be fixed?

What, then, can documentation authors and others do about this?

An easy first step is to not include the optional invariant sections in your documentation, since they are not required by the license, but are simply an option open to authors.

Unfortunately this alone is not enough, as other clauses of the GFDL render all GFDL documentation non-free. As a consequence, other licenses should be investigated; generally it is probably simplest to choose either the GNU General Public License (for a copyleft license) or the BSD or MIT licenses (for a non-copyleft license).

As most GFDL documentation is made available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation, the Free Software Foundation is able to remedy these problems by changing the license. The problems discussed above require relatively minor changes to the GFDL — allowing invariant sections to be removed, allowing transparent copies to be made available concurrently, and moderating the restrictions on technical measures. Unfortunately, while members of the Debian Project have been in contact with the FSF about these concerns for the past four years, these negotiations have not come to any conclusion to date.

Amendment Proposer A

Adeodato Simó [[email protected]]

Amendment Seconds A

- Anthony Towns [[email protected]]

- Osamu Aoki [[email protected]]

- Christopher Martin [[email protected]]

- Wesley J. Landaker [[email protected]]

- Wouter Verhelst [[email protected]]

- Hamish Moffatt [[email protected]]

- Pierre Habouzit [[email protected]]

- Marc 'HE' Brockschmidt [[email protected]]

- Anibal Monsalve Salazar [[email protected]]

- Isaac Clerencia [[email protected]]

- Moritz Muehlenhoff [[email protected]]

- Zephaniah E. Hull [[email protected]]

- Christian Perrier [[email protected]]

- Martin Michlmayr [[email protected]]

- Christoph Berg [[email protected]]

Amendment Text A

Choice 2. The actual text of the amendment is:

This is the position of the Debian Project about the GNU Free Documentation License as published by the Free Software Foundation:

-

We consider that the GNU Free Documentation License version 1.2 conflicts with traditional requirements for free software, since it allows for non-removable, non-modifiable parts to be present in documents licensed under it. Such parts are commonly referred to as

invariant sections

, and are described in Section 4 of the GFDL.As modifiability is a fundamental requirement of the Debian Free Software Guidelines, this restriction is not acceptable for us, and we cannot accept in our distribution works that include such unmodifiable content.

-

At the same time, we also consider that works licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License that include no invariant sections do fully meet the requirements of the Debian Free Software Guidelines.

This means that works that don't include any Invariant Sections, Cover Texts, Acknowledgements, and Dedications (or that do, but permission to remove them is explicitly granted), are suitable for the main component of our distribution.

-

Despite the above, GFDL'd documentation is still not free of trouble, even for works with no invariant sections: as an example, it is incompatible with the major free software licenses, which means that GFDL'd text can't be incorporated into free programs.

For this reason, we encourage documentation authors to license their works (or dual-license, together with the GFDL) under the same terms as the software they refer to, or any of the traditional free software licenses like the GPL or the BSD license.

Amendment Proposer B

Anton Zinoviev [[email protected]]

Amendment Seconds B

- Raphael Hertzog [[email protected]]

- Xavier Roche [[email protected]]

- Wesley J. Landaker [[email protected]]

- Romain Francoise [[email protected]]

- Moritz Muehlenhoff [[email protected]]

- Craig Sanders [[email protected]]

Amendment Text B

Choice 3. The actual text of the amendment is:

GNU Free Documentation License protects the freedom, it is compatible with Debian Free Software Guidelines

0: Summary

This is the position of Debian Project about the GNU Free Documentation License as published by the Free Software Foundation:

We consider that works licensed under GNU Free Documentation License version 1.2 do fully comply both with the requirements and the spirit of Debian Free Software Guidelines.

Within Debian community there has been a

significant amount of uncertainty about the GNU

Free Documentation License (GFDL), and whether

it is, in fact, a free

license. This

document attempts to explain why Debian's answer

is yes

.

1: What is the GFDL?

The GFDL is a license written by the Free Software Foundation, who use it as a license for their own documentation, and promote it to others. It is also used as Wikipedia's license. To quote the GFDL's Preamble:

The purpose of this License is to make a manual, textbook, or other functional and useful document

freein the sense of freedom: to assure everyone the effective freedom to copy and redistribute it, with or without modifying it, either commercially or noncommercially. Secondarily, this License preserves for the author and publisher a way to get credit for their work, while not being considered responsible for modifications made by others.

This License is a kind of

copyleft, which means that derivative works of the document must themselves be free in the same sense. It complements the GNU General Public License, which is a copyleft license designed for free software.

(2) The Invariant Sections — Main Objection Against GFDL

One of the most widespread objections against GFDL is that GFDL permits works covered under it to include certain sections, designated as invariant. The text inside such sections can not be changed or removed from the work in future.

GFDL places considerable constraints on the purpose of texts that can be included in an invariant section. According to GFDL all invariant sections must be also secondary sections, i.e. they meet the following definition

A Secondary Section is a named appendix or a front-matter section of the Document that deals exclusively with the relationship of the publishers or authors of the Document to the Document's overall subject (or to related matters) and contains nothing that could fall directly within that overall subject. [...] The relationship could be a matter of historical connection with the subject or with related matters, or of legal, commercial, philosophical, ethical or political position regarding them.

Consequently the secondary sections (and in particular the invariant sections) are allowed to include only personal position of the authors or the publishers to some subject. It is useless and unethical to modify somebody else's personal position; in some cases this is even illegal. For such texts Richard Stallman (the founder of the Free Software Movement and the GNU project and author of GFDL) says [1]:

The whole point of those works is that they tell you what somebody thinks or what somebody saw or what somebody believes. To modify them is to misrepresent the authors; so modifying these works is not a socially useful activity. And so verbatim copying is the only thing that people really need to be allowed to do.

This feature of GFDL can be opposed to the following requirement of Debian Free Software Guidelines:

3. Derived Works

The license must allow modifications and derived works, and must allow them to be distributed under the same terms as the license of the original software.

It is naive to think that in order to fulfil this requirement of DFSG the free licenses have to permit arbitrary modifications. There are several licenses that Debian has always acknowledged as free that impose some limitations on the permitted modifications. For example the GNU General Public License contains the following clause:

If the modified program normally reads commands interactively when run, you must cause it, when started running for such interactive use in the most ordinary way, to print or display an announcement including an appropriate copyright notice and a notice that there is no warranty (or else, saying that you provide a warranty) and that users may redistribute the program under these conditions, and telling the user how to view a copy of this License.

The licenses that contain the so called advertising clause give us another example:

All advertising materials mentioning features or use of this software must display the following acknowledgement:

This product includes software developed by ...

Consequently when judging whether some license is free or not, one has to take into account what kind of restrictions are imposed and how these restrictions fit to the Social Contract of Debian:

4. Our priorities are our users and free software

We will be guided by the needs of our users and the free software community. We will place their interests first in our priorities.

Currently GFDL is a license acknowledged as

free by the great mass of the members of the

free software community and as a result it is

used for the documentation of great part of

the currently available free programs. If

Debian decided that GFDL is not free, this

would mean that Debian attempted to impose on

the free software community alternative

meaning of free software

, effectively

violating its Social Contract with the free

software community.

We should be able to improve the free software and to adapt it to certain needs and this stays behind the requirement of DFSG for modifiability. GFDL allows everybody who disagrees with a personal position expressed in an invariant section to add their own secondary section and to describe their objections or additions. This is a reasonable method to improve the available secondary sections, a method that does not lead to misrepresenting the authors opinion or to censorship.

(3) Transparent copies

Another objections against GFDL is that according to GFDL it is not enough to just put a transparent copy of a document alongside with the opaque version when you are distributing it (which is all that you need to do for sources under the GPL, for example). Instead, the GFDL insists that you must somehow include a machine-readable Transparent copy (i.e., not allow the opaque form to be downloaded without the transparent form) or keep the transparent form available for download at a publicly accessible location for one year after the last distribution of the opaque form.

The following is what the license says (the capitalisations are not from the original license):

You must either include a machine-readable Transparent copy ALONG with each Opaque copy, or state IN OR WITH each Opaque copy a computer-network location from which the general network-using public has access to download using public-standard network protocols a complete Transparent copy of the Document, free of added material.

Consequently the license requires distribution of the transparent form ALONG with each opaque copy but not IN OR WITH each opaque copy. It is a fact confirmed by Richard Stallman, author of GFDL, and testified by the common practice, that as long as you make the source and binaries available so that the users can see what's available and take what they want, you have done what is required of you. It is up to the user whether to download the transparent form.

If the transparent copy is not distributed along with the opaque copy then one must take reasonably prudent steps to ensure that the Transparent copy will remain accessible from Internet at a stated location until at least one year. In these circumstances the requirement of GPL appears to be even more severe — a written offer, valid for at least three years, to give any third party a complete machine-readable copy of the corresponding source code.

(4) Digital Rights Management

The third objection against GFDL arises from the measures in Section 2 that attempt to overcome Digital Rights Management (DRM) technologies. According to some interpretations of the license, it rules out distributing copies on DRM-protected media, even if done in such a way as to give users full access to a transparent copy of the work; and, as written, it also potentially disallows encrypting the documentation, or even storing it on a file system that supports permissions.

In fact, the license says only this:

You may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies you make or distribute

This clause disallows the distribution or storage of copies on DRM-protected media only if a result of that action will be that the reading or further copying of the copies is obstructed or controlled. It is not supposed to refer the use of encryption or file access control on your own copy.

Consequently the measures of the license against the DRM technologies are only a way to ensure that the users are able to exercise the rights they should have according to the license. Because of that, these measures serve similar purpose to the measures taken in the GNU General Public License against the patents:

If a patent license would not permit royalty-free redistribution of the Program by all those who receive copies directly or indirectly through you, then the only way you could satisfy both it and this License would be to refrain entirely from distribution of the Program.

We do not think that this requirement of GPL makes GPL covered programs non-free even though it can potentially make a GPL-covered program undistributable. Its purpose is against misuse of patents. Similarly, we do not think that GFDL covered documentation is non-free because of the measures taken in the license against misuse of DRM-protected media.

Quorum

With 972 developers, we have:

Current Developer Count = 972

Q ( sqrt(#devel) / 2 ) = 15.5884572681199

K min(5, Q ) = 5

Quorum (3 x Q ) = 46.7653718043597

- Option1 Reached quorum: 223 > 46.7653718043597

- Option2 Reached quorum: 272 > 46.7653718043597

- Option3 Reached quorum: 133 > 46.7653718043597

Data and Statistics

For this GR, as always statistics are being gathered about ballots received and acknowledgements sent periodically during the voting period. Additionally, the list of voters is available. Also, the tally sheet may also be viewed (Note that while the vote is in progress it is a dummy tally sheet).

Majority Requirement

Since amendment B would require modification of a foundation document, namely, the Social Contract, it requires a 3:1 majority to pass. DFSG article 3 would need to be changed, or at least clarified. As it reads, it states that licenses a work is available under must allow modifications of the work.

- Option1 passes Majority. 1.874 (223/119) > 1

- Option2 passes Majority. 3.200 (272/85) > 1

- Dropping Option3 because of Majority. 0.649 (133/205) <= 3

Outcome

The winner

- Option 2

GFDL-licensed works without unmodifiable sections are free

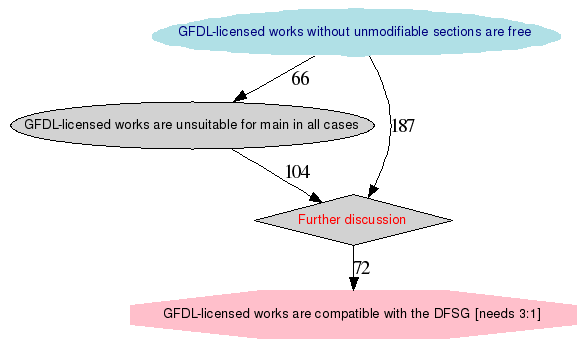

In the graph above, any pink colored nodes imply that the option did not pass majority, the Blue is the winner. The Octagon is used for the options that did not beat the default. In the following table, tally[row x][col y] represents the votes that option x received over option y. A more detailed explanation of the beat matrix may help in understanding the table. For understanding the Condorcet method, the Wikipedia entry is fairly informative.

- Option 1

GFDL-licensed works are unsuitable for main in all cases

- Option 2

GFDL-licensed works without unmodifiable sections are free

- Option 3

GFDL-licensed works are compatible with the DFSG [needs 3:1]

- Option 4

Further discussion

| Option | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Option 1 | 145 | 226 | 223 | |

| Option 2 | 211 | 266 | 272 | |

| Option 3 | 117 | 76 | 133 | |

| Option 4 | 119 | 85 | 205 | |

Looking at row 2, column 1, GFDL-licensed works without unmodifiable sections are free

received 211 votes over GFDL-licensed works are unsuitable for main in all cases

Looking at row 1, column 2, GFDL-licensed works are unsuitable for main in all cases

received 145 votes over GFDL-licensed works without unmodifiable sections are free.

Pair-wise defeats

- Option 2 defeats Option 1 by ( 211 - 145) = 66 votes.

- Option 1 defeats Option 4 by ( 223 - 119) = 104 votes.

- Option 2 defeats Option 4 by ( 272 - 85) = 187 votes.

The Schwartz Set contains

- Option 2

GFDL-licensed works without unmodifiable sections are free

Debian uses the Condorcet method for votes.

Simplistically, plain Condorcets method

can be stated like so :

Consider all possible two-way races between candidates.

The Condorcet winner, if there is one, is the one

candidate who can beat each other candidate in a two-way

race with that candidate.

The problem is that in complex elections, there may well

be a circular relations ship in which A beats B, B beats C,

and C beats A. Most of the variations on Condorcet use

various means of resolving the tie. See

Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping

for details. Debian's variation is spelled out in the

the constitution,

specifically, A.6.

Manoj Srivastava